The First Law: A robot may not injure a human being or, through inaction, allow a human being to come to harm.

Isaac Asimov’s ‘Three Laws of Robotics’, introduced in 1942’s “Runaround” (Hyperlink 1):

The Second Law: A robot must obey the orders given it by human beings except where such orders would conflict with the First Law.

The Third Law: A robot must protect its own existence as long as such protection does not conflict with the First or Second Laws.

Reading Asimov, it is clear the discourse between the literary and scientific disciplines is thick with tradition…

… for instance, founding empiricists such as Robert Boyle utilised literary techniques to develop and engage the public’s role as “virtual witnesses” (Hyperlink 2) whilst demonstrating the character of the author as modest and reliable. Samsung exemplified the “prior art” defence arguing that Stanley Kubrick (assisted by science fiction novelist Arthur C. Clarke) invented the personal tablet computer, not Apple (Hyperlink 3). Scientific models and communication have also been integrated into elements of the New Formalist literary movement, reinterpreting the styles, diagrams and metaphors of the scientific form to aid with the communication of abstract themes (Hyperlink 4). Techniques and forms flow between the disciplines, and many fundamental communicative challenges are shared.

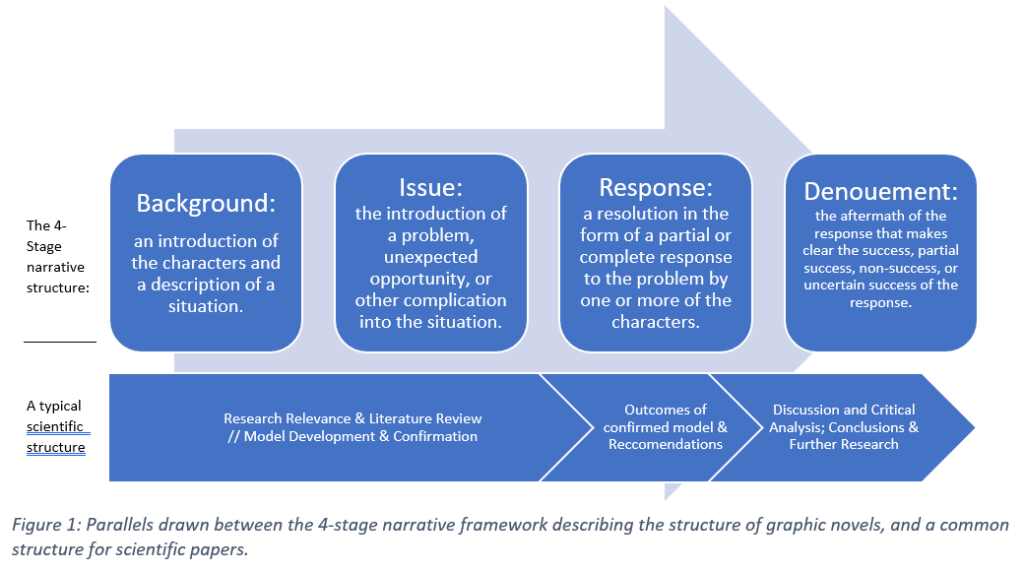

Introducing the 4-stage narrative framework (common within graphic novels) to scientific forms requires no adaptation (Figure 1):

This structure addresses some relevant traits shared by scientific literature and graphic novels/comic books: a requirement for clear, concise texts; developed, but sometimes competing bodies of knowledge (the literary canon); and the frequent addition of alien “undiscovered” concepts. Above, we see both structures start by communicating the shared set of assumptions and models that ground the narrative. Figure 1 shows both structures end not with the response and resolution, but by acknowledging the interplay between the reader’s existing bodies of knowledge and the bodies of knowledge created or modified within the narrative.

Both the scientific and the 4-stage narrative structures recognise that individual works often contribute just a fragment to the arcs of comic book canons, or to our scientific knowledge. However, this iterative, compartmentalised approach to granularity allows for the dynamic exploration of new concepts whilst addressing their resultant uncertainties.

Unsurprisingly then, narrative concepts already exist within the scientific framework, in the form of the “Sociotechnical Imaginaries”, described as:

“[C]ollectively imagined forms of social life and social order reflected in the design and fulfillment of nation-specific scientific and/or technological projects”.

Jasanoff & Kim, 2009 (Hyperlink 5)

I would like challenge this formulation. Here the role of the narrative is strictly to assist in informing the design of these projects, and to motivate the design’s fulfillment. Little attention is given to the competing normative perspectives that can occur in creating these visions, or in reacting to projects as they are constructed. Nor is there adequate focus on the underlying power dynamics influencing which narratives emerge as “collectively imagined”.

What of the need to critique pathways and projects that are already underway?

The “sociotechnical imaginaries” are often limited to positive visions, rather than the interrogatory narratives imbued into works like Rachel Carson’s ‘Silent Spring’ or Isaac Asimov’s ‘Three Laws of Robotics’. By limiting the concept only to emergent narratives, the “sociotechnical imaginary” excludes both the narratives derived from current lived experience, and the dynamism of large-scale, shifting social narratives. I would argue for the evolution of the “sociotechnical imaginary” concept within the co-productionist perspective; to better integrate Jasanoff’s emphasis of reflexive analysis and interpretation within co-production; and acknowledge competition between sociotechnical narratives.

As always, I defer to Asimov. In the spirit of dynamism, he added the fourth, or ‘Zeroth Law’ of robotics:

A robot may not harm humanity, or, by inaction, allow humanity to come to harm.

Foundation and Earth (1986, Hyperlink 6)

In case more Asimov-based arguments were needed for considering subjectivity and diversity in the creation of collective knowledge and narratives…

The Zeroth Law was first incorporated into Asimov’s novels not by Asimov, but by French translator Jacques Brécard:

“A robot may not harm a human being, unless he finds a way to prove that ultimately the harm done would benefit humanity in general!”

Jacques Brécard, reinterpreting character Elijah Baley’s dialogue in his translation of Asimov’s “The Caves of Steel” (Hyperlink 7)

Later stated explicitly, this ‘Zeroth Law’ allowed Asimov to deal with abstraction and epistemological uncertainty, much like the techniques of Thomas Hobbes and the New Formalists, and like Jasanoff’s vision of pluranimous co-production, it was used to critique the need for consensus. I will leave you once again, with messy questions regarding the true place of narratives in the sciences, and the timeless words of Asimov:

Trevize frowned. “How do you decide what is injurious, or not injurious, to humanity as a whole?”

Foundation and Earth (1986, Hyperlink 6)

“Precisely, sir,” said Daneel. “In theory, the Zeroth Law was the answer to our problems. In practice, we could never decide. A human being is a concrete object. Injury to a person can be estimated and judged. Humanity is an abstraction.”

Hyperlinks and Further Reading:

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Three_Laws_of_Robotics

- https://royalsocietypublishing.org/doi/10.1098/rsnr.2018.0051

- https://www.cnet.com/news/samsung-says-2001-a-space-odyssey-invented-the-tablet-not-apple/

- https://muse.jhu.edu/article/734309/pdf

- https://www.researchgate.net/publication/227303577_Containing_the_Atom_Sociotechnical_Imaginaries_and_Nuclear_Power_in_the_United_States_and_South_Korea

- https://openlibrary.org/works/OL46347W/Foundation_and_Earth

- Asimov, Isaac (1952). The Caves of Steel. Doubleday., translated by Jacques Brécard as Les Cavernes d’acier. J’ai Lu Science-fiction. 1975. ISBN 978-2-290-31902-4. Available via Hyperlink: https://www.books-by-isbn.com/authors/isaac/asimov/

An introduction to Co-Production: https://journals.plos.org/plosbiology/article?id=10.1371/journal.pbio.2001403

For Jasanoff and Kim’s updated work:

https://press.uchicago.edu/ucp/books/book/chicago/D/bo20836025.html