The Who and the How

In preparatory discussions for these blogs, fellow writer and activist Meg Watts forwarded me an insightful passage from ‘An interview with Benjamin Myers’, in the counterculture zine ‘Weird Walk’:

“’Wild’, [my neighbour] told me, wasn’t a useful term. He pointed to a small cluster of trees a half-mile away: ‘Left to its own devices, all this land wants to be that. And that isn’t exactly right anymore.’“

Weird Walk; Issue 2; p23(Hyperlink 1)

Occurring in “Constable Country”, in Suffolk, so named after the bucolic painter John Constable, this pastoral perspective is uniquely Western. Alongside losing our landscape’s natural capital, we may have lost other diverse normative perspectives of how our landscapes “ought” to be. The dominance of enclosed agriculture, and its idyll, is pervasive. We must consider the power dynamics that propagated these normative perspectives and discern who and how will we answer the question: “What do we need from our landscape?”.

A traditional, “linear perspective”, sets knowledge makers as distinct from the general public, in order to generate and codify “truths” to be distributed from the top down. This has been the case for most of human history, where religious figures or knowledge-holders may discern their “truths” from the environment or texts, and the sciences have been treated no differently for most of their duration. Separating social influence was as fundamental to the communication of the Ten Commandments as the establishment of Boyle’s Law.

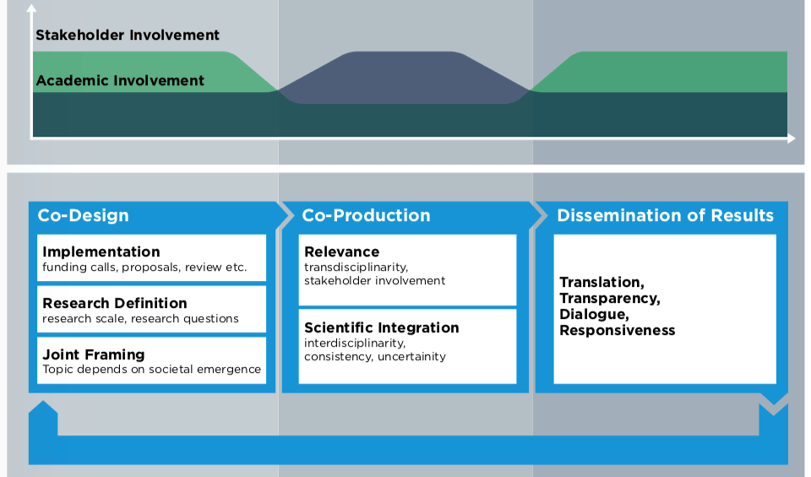

At the opposite end of the spectrum, where science and society “make things together”, lie the “co-productionist” perspectives. Often framed in terms of obtaining more relevant knowledge, that is more representative of the experiences of the public at large, “Common Sense” co-production brings society into the sciences without changing the positions of institutions like the Royal Society as “knowledge makers”.

Sheila Jasanoff presents an alternative alternative, her co-production focusing instead on society’s role in describing, analysing and interpreting in order to co-produce knowledge. Much attention is devoted to systems that better represent the complexity of knowledge, regarding public perceptions of how the world “is”, and how it “ought” to be, not in the pursuit of a singular robust result, but rather multifaceted solutions with many shades of “rightness”, and a process that is itself flexible and inclusive. Novel approaches to considering who answers the questions the public pose have never been more necessary than now.

As for the how to answer our question… consensus is only one of many group decision-making techniques, and many support the novel approach known as “post-normal science”, applied where “facts [are] uncertain, values in dispute, stakes high and decisions urgent” (Funtowicz, S. and Ravetz, J., 1993. “Science for the post-normal age”, Futures, 31(7): 735-755.). Relevant, amongst our ongoing environmental crises, this post-normal approach disputes more of the process of science, focusing as much on “who gets funded, who evaluates quality, who has the ear of policy – as on the facts of science” (Hulme, 2007; Hyperlink 2)

Available at: http://old.futureearth.org/sites/default/files/Future-Earth-Design-Report_web.pdf

Both post-normal and co-productionist approaches are identifiable in research programmes such as “Future Earth”, which hosts research topics ranging from agriculturally-initiated migration (Hyperlink 3), to modelling future land cover change (Hyperlink 4). The advantages were best described by Prof. Hans Hurni:

“Studies on land degradation were first done mainly by bio-physical sciences […] The roles of land users were addressed only at a later stage when it became clear that the problems needed to be addressed by them. [transitioning] to transdisciplinary approaches, where groups of scientists would work with local land users and concerned stakeholders and include their knowledge systems in finding appropriate solutions”

Prof. Hans Hurni. Interview available at: https://futureearth.org/2015/10/08/qa-with-hans-hurni/

How far we have travelled away from our cosy physical science lairs… The alternative local knowledge systems Hurni described are often holistic worldviews derived from multiple generation’s engagement with the same landscape. Many describe the direct connections that exist between human lifestyle and the land. Though these visceral relationships are integrated in Traditional Ecological Knowledge (TEK), these perspectives were considered revolutionary when introduced by scholars such as Jasanoff, as the following quotes illustrate:

‘‘the ways in which we know and represent the world (both nature and society) are inseparable from the ways in which we choose to live in it’’

Jasanoff (2004) (Hyperlink 5)

“The major difference between Indigenous and non-Indigenous conceptions of TEK is that Indigenous people see TEK as much more than a ‘body of knowledge’; rather, it is a ‘way of living’, it is about how one relates to Mother Earth”

MacGregor (2018) (Hyperlink 6)

It is clear we need to address the ways that we produce knowledge and live amongst our landscapes. The increasing diversity of approaches, as discussed above, offers hope. Our current opportunity to democratise sociotechnical structures is unprecedented, but power imbalances persist. Many communities holding TEK or excluded from the scientific narrative will be amongst the worst affected by climate change. It is these voices we need to listen to and consider in order to properly ask “What do we need from our landscape?”.

Hyperlinks:

- https://www.outsidersstore.com/weird-walk-zine-issue-2-189162 (p.23)

- https://www.theguardian.com/society/2007/mar/14/scienceofclimatechange.climatechange

- http://old.futureearth.org/blog/2019-apr-26/when-land-needed-people-are-not

- http://old.futureearth.org/blog/2019-apr-26/uncertainties-future-global-land-use-and-land-cover-change

- https://www.taylorfrancis.com/books/e/9780203413845

- https://www.routledge.com/Companion-to-Environmental-Studies-1st-Edition/Castree-Hulme-Proctor/p/book/9781138192201 (p.704)