“[…] the dayfly (ephémeron) moves with four feet and four wings; […] exceptional not only in regard to the duration of its existence, whence it receives its name, a quadruped it has wings also.“

— Aristotle (the famous one!), History of Animals 490a–b.

Sometimes it is hardest to objectively consider the topics that are closest to the heart, or that may impact your life significantly and personally. Here we will look at a case that is likely neither of those, for most readers: the case of Aristotle and the four-legged fly.

Apologies to any entomologists….

Many argue science’s core tenet is skepticism, but Steven Shapin counters that science is more reliant on trust and diligence than most other social systems (Hyperlink 1); many scientists may question the freshness of the milk on their doorstep more so than the chemicals in their lab.

Collective knowledge is a social construction requiring curation, and is ever shifting (see half-life of knowledge, Hyperlink 2), yet this blog will cover the controversy of the mayfly’s legs, and reveal how for hundreds of years an “untruth” persisted.

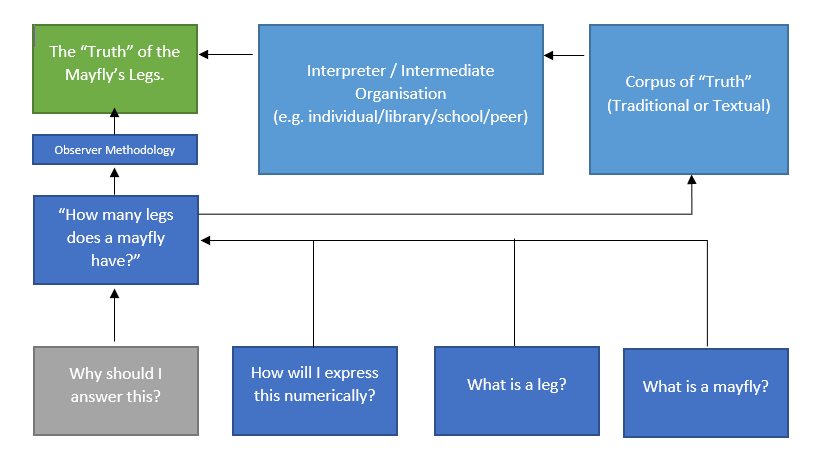

Below is a diagram showing two possible routes to the “truth” of the mayfly’s legs; firstly, Boyle’s preferred empirical approach (stating that rationally acceptable beliefs are only justifiable or knowable through experience), secondly, a traditional academic approach (where knowledge imparts from a culturally-derived source).

Considering the elements, it is clear that in the case of the academic route that the Corpus referred to has been constructed socially, and belongs to institutions who curate and/or interpret the texts or traditions. A strident empiricist may argue that the observer’s methodology determines the quality of the truth, and that where the proper methodology yields replicable results, a “pure” truth has been revealed, unsullied by social influence.

Looking at the lowest layer of this graph, we see how the question itself is composed of semantic elements (dark blue), difficult to unpick from social influence; and an element of significance that motivates the interested party in carrying out an investigation.

Simply, Aristotle stated mayfly’s have four legs, a “truth” that would very much be disputed today, yet was apparently repeated in natural history texts for thousands of years, often extrapolated to a statement about all flies (Hyperlink 3) (Aristotle did in fact distinguish insects). As Aristotle did not use a distinct numerical system, and was by all accounts an astute observer, we should consider where the lack of consensus arises, and whether the correct questions were asked:

“What is a leg?”:

Aristotle counted and communicated “leggedness” based on functionality, particularly utilisation of limbs for walking/locomotion. The forelegs of many adult mayfly are specialised for mating (the sole task of an adult mayfly), and thus were not counted (Hyperlink 4). Scientific consensus, and possibly even society, does not use the same functional definition of legs as Aristotle, and these socially-constructed semantics are arrived at by deliberation and communicated in socially-defined languages, and thus are not universal across time and space.

“What is a mayfly?”:

Aristotle refers to “ephémeron“, of which 2000+ species are now recognised, and often referred to mayflies as “the shortest-lived animal”, “emerging from sacks” (Hyperlink 5). This belies the fact that Aristotle had not recognised the juvenile state of the mayfly, lasting up to two years, in which the role of the forelegs is unrelated to reproduction, but is utilised for locomotion: a “leg” by Aristotle’s own definition.

Concluding…

…despite mayflies existing in their many-legged states as a matter of fact, we can see how each different socially-determined formulation of the proposition lead to divergence in the “truth” of the matter. Aristotle’s answer is no less valid to his peers than our’s is now, regardless, it is of little significance to most at any period in time. Perhaps this is exactly why the “mistruth” persisted with such little opposition for so long, and was so readily accepted.

Hobbes would agree, arguing that where knowledge is considered significant, publics resist inculcation, and should rationalise their own formulation of the question, and produce their mayfly knowledge collectively, with all the nuance that may bring.

Boyle would probably argue Aristotle’s methodology was flawed and suffocate the poor animal with his air pump just to check…

Hyperlinks:

- https://www.cbc.ca/radio/ideas/how-to-think-about-science-part-16-1.464997

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Half-life_of_knowledge

- https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC1299297/

- https://scienceblogs.com/evolvingthoughts/2008/09/16/aristotle-on-the-mayfly

- https://books.google.co.uk/books?id=CU4gBQAAQBAJ&pg=PA260&lpg=PA260&dq=aristotle+shortest+lived+animal+mayfly&source=bl&ots=XASzRJ9k2L&sig=ACfU3U1Lct_jMnlYZ03DvQxYAOAE39FFhA&hl=en&sa=X&ved=2ahUKEwjQ9NeFuZfnAhUMGsAKHQXTA8wQ6AEwC3oECAsQAQ#v=onepage&q=aristotle%20shortest%20lived%20animal%20mayfly&f=false